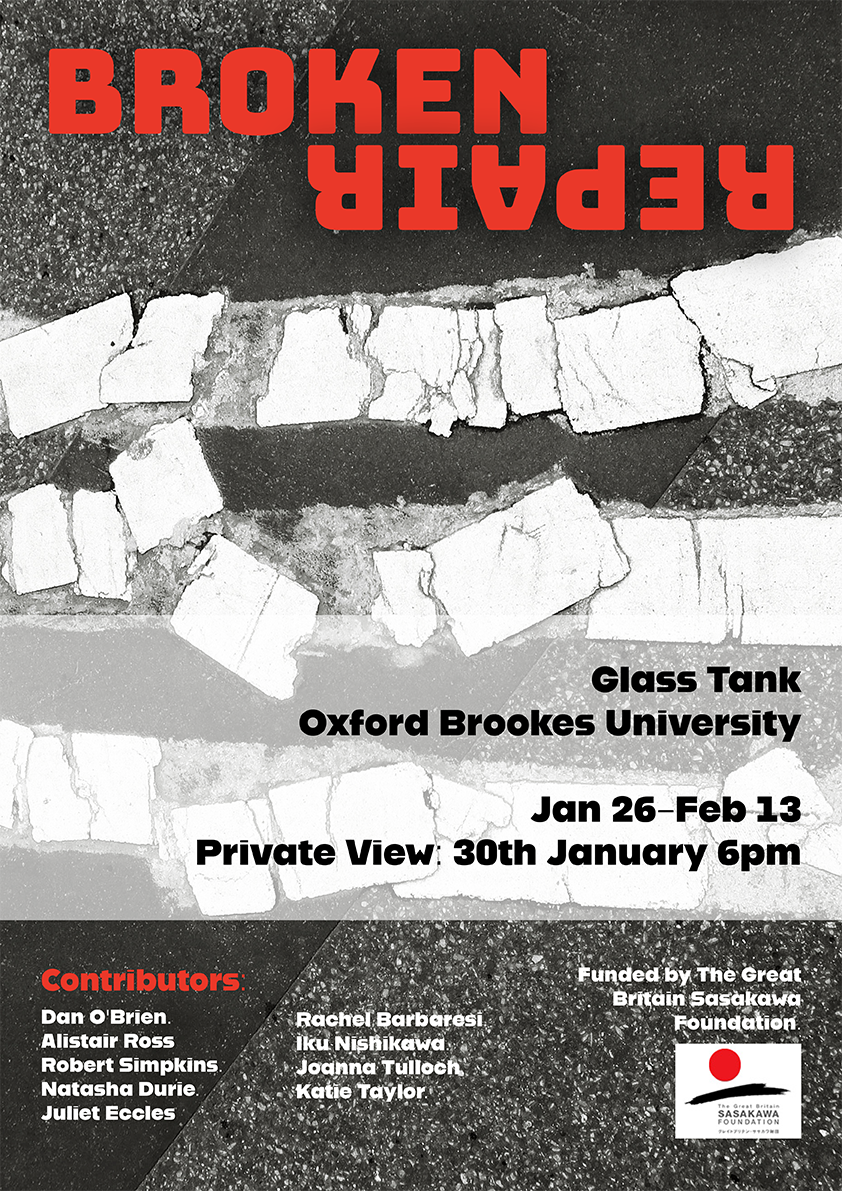

Brokenness and repair

Brokenness and Repair Exhibition at Oxford Brookes University

26 January 2026, 9:00 am to 5:00 pm

Reception event 30th January from 5pm

The Glass Tank, Oxford Brookes University

I am participating in the group exhibition Brokenness and Repair at Oxford Brookes University, an exhibition that asks a deceptively simple question: what does it mean to care when something is broken?

Inspired in part by the Japanese practice of kintsugi, where fractures are neither hidden nor erased but attended to with care. The exhibition opens a wider conversation across cultures, disciplines, and lived experience. Brokenness here is not framed as failure, but as a condition of being human: a state that asks for attention, patience, and time.

This framing sits at the very heart of Shifting States.

Brokenness as a State, Not a Problem

Much of contemporary culture urges us to fix, optimise, or move on quickly. Yet life transitions, divorce, loss, identity change, displacement, rarely conform to neat arcs of recovery. They unfold slowly, unevenly, often without resolution.

Shifting States begins from the same premise as this exhibition: that brokenness is not something to be rushed through or repaired back into its former shape. It is a liminal state, a threshold where something has ended, but what comes next is not yet clear.

The works I am presenting in Brokenness and Repair emerge directly from this ground.

Making as Attending, Not Mending

At the centre of my installation is Nigredo (2025): a dense, almost-black circle of needle-felted wool. The process of needle felting—repetitive, rhythmic, physically demanding, became a way of metabolising emotional intensity during the dissolution of my marriage. As the fibres compacted, the wool crossed a point of no return; it could no longer be undone.

Embedded at the top of this dense mass is my wedding ring. A symbol of eternity, now immobilised. It cannot move, cannot be retrieved, cannot return to circulation. The ring becomes a marker of an identity that has fractured and can no longer function as it once did.

This work does not attempt repair in the traditional sense. It does not restore. Instead, it holds, grief, rupture, finality, without resolution.

Alongside this, I am exhibiting a series of pewter cast objects. Pewter, an ancient alloy of tin, carries strong alchemical associations with renewal and transformation. Some casts are formed inside oyster shells: rough and protective on the outside, smooth and luminous within. Others include a rough gravestone casting bearing the single word wife, its surface uneven, grainy, and incomplete.

These objects sit in a state of suspension, molten, then suddenly fixed—mirroring the instability of transition itself.

Transitional Objects and the Work of Shifting States

With Shifting States, I work with the idea of transitional objects: things that allow us to externalise emotional thresholds when language alone is insufficient. Objects that do not resolve experience, but make it bearable, holdable, and visible.

The works in this exhibition operate in exactly this way. They do not offer closure or redemption narratives. They resist the idea that repair means returning to what was. Instead, they insist that repair may mean learning to stay with discomfort long enough for something new to take shape.

Transition is not a detour, but a condition of contemporary life

That making can be a form of listening rather than producing

That care is an active, material practice

And that brokenness can be a generative in-between, not a deficit

The Brokenness and Repair exhibition creates a shared space for reflection across sculpture, sound, pottery, and image, inviting viewers not to admire repair from a distance, but to recognise themselves within it. ithout certainty, but with intention.